By: Sara Carmichael Water Fluoridation Coordinator Iowa Department of Public Health

Tooth decay is the most common, chronic disease among children and the elderly. One in 5 people has untreated decay, also known as cavities,[1] which severely impacts social development, self-esteem, and overall quality of life.

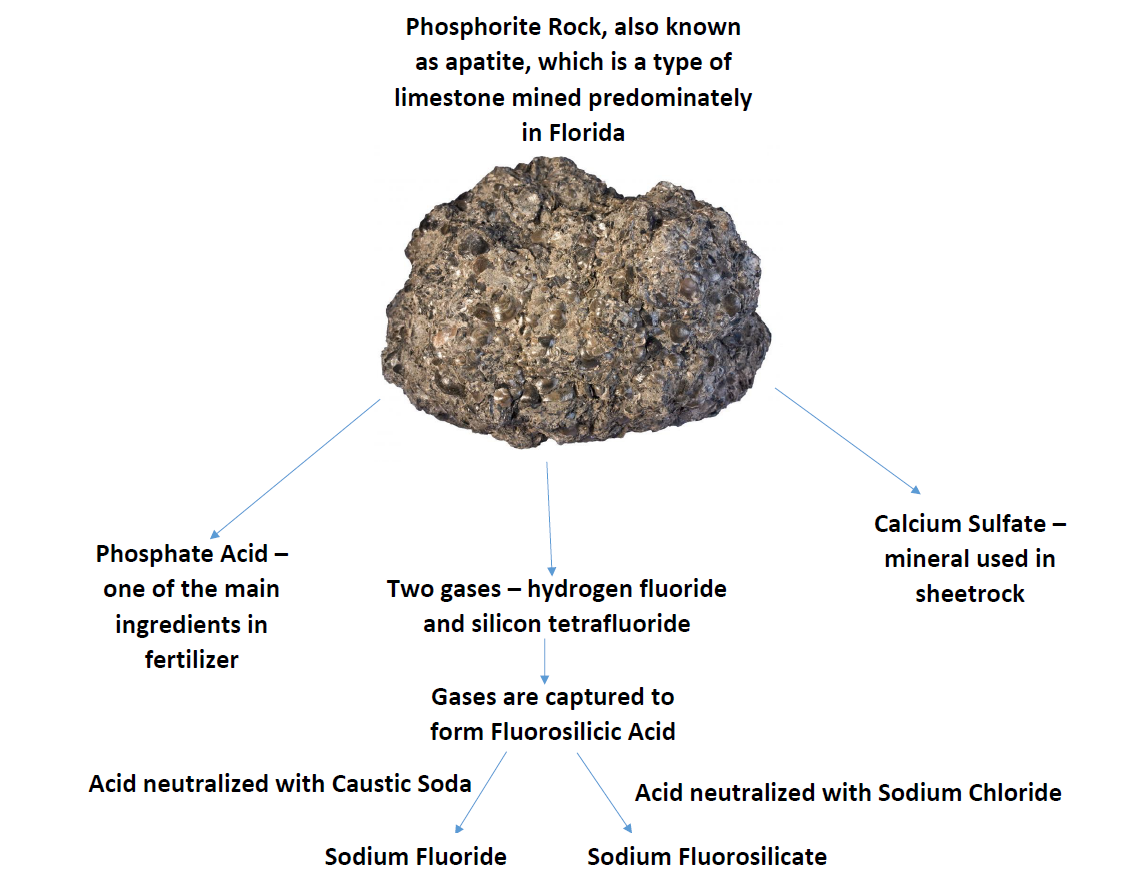

But cavities are preventable! Besides practicing good oral hygiene like brushing twice a day for two minutes, flossing, and eating a healthy diet, an easy way to prevent cavities is by drinking optimally fluoridated water. The adjustment of fluoride levels in drinking water is called Community Water Fluoridation (CWF). Best of all, everyone benefits from water fluoridation, regardless of income, education, or place of residence. Fluoride is naturally present in all water sources, including surface water, groundwater, and  oceans. Water fluoridation is the adjustment, up or down, of the natural fluoride to a recommended level of 0.7 mg/L to prevent tooth decay. The fluoride additives are produced from phosphorite rock, a type of limestone. The mechanism of production can be seen in the following diagram. All fluoride additives are thoroughly tested, regulated, and determined safe by the Environmental Protection Agency and independent organizations, including NSF International and Underwriters Laboratories.

oceans. Water fluoridation is the adjustment, up or down, of the natural fluoride to a recommended level of 0.7 mg/L to prevent tooth decay. The fluoride additives are produced from phosphorite rock, a type of limestone. The mechanism of production can be seen in the following diagram. All fluoride additives are thoroughly tested, regulated, and determined safe by the Environmental Protection Agency and independent organizations, including NSF International and Underwriters Laboratories.

Adding fluoride to water is managed by the local water operator to make sure the optimal amount is used. There are three additives for water fluoridation. The decision on which additive to use is based on cost, space, availability, and equipment. The three additives are

- Fluorosilicic acid: a water-based solution used by most water systems in the United States.

- Sodium fluorosilicate: a dry salt additive, dissolved into a solution before being added to the water.

- Sodium fluoride: a dry salt additive, typically used in smaller water systems, and dissolved into a solution before being added to the water.

Currently, about 70% of Iowans have access to optimally fluoridated water. If you are on a community water system and want to know the level of fluoride, visit the CDC’s website, My Water’s Fluoride, at https://nccd.cdc.gov/DOH_MWF.

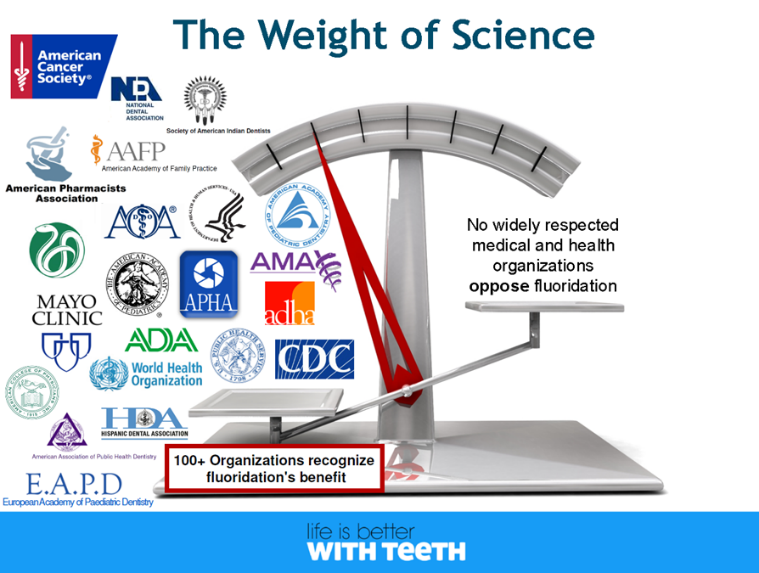

Community water fluoridation is so effective at preventing decay that the Centers for  Disease Control and Prevention named it one of 10 public health achievements of the 20th Century. Study after scientific study has shown that CWF reduces the amount of cavities seen in baby teeth by at least 35% and reduces decay in permanent teeth by at least 25%.[2] Over 100 national and international organizations support CWF, including the American Cancer Society, American Academy of Family Practice, and World Health Organization.

Disease Control and Prevention named it one of 10 public health achievements of the 20th Century. Study after scientific study has shown that CWF reduces the amount of cavities seen in baby teeth by at least 35% and reduces decay in permanent teeth by at least 25%.[2] Over 100 national and international organizations support CWF, including the American Cancer Society, American Academy of Family Practice, and World Health Organization.

For more information, please contact Sara Carmichael, Water Fluoridation Coordinator at the Iowa Department of Public Health, at 515-204-3450 or sara.carmichael@idph.iowa.gov

[1] https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/costofdelaywebpdf.pdf

[2] http://www.cochrane.org/CD010856/ORAL_water-fluoridation-prevent-tooth-decay